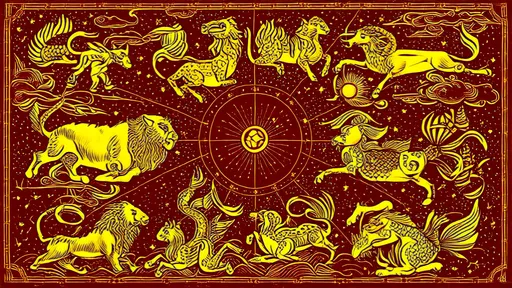

The tradition of New Year paintings, known as Nianhua in Chinese, has long been intertwined with cultural symbolism, storytelling, and even celestial themes. Among these, the depiction of zodiac signs and constellations stands out as a fascinating blend of folk art and astrological belief. These artworks, often vibrant and meticulously detailed, serve not only as decorative pieces but also as carriers of ancient wisdom and seasonal rituals. The connection between New Year paintings and the stars reveals a deeper layer of cultural significance, where the heavens above mirror the hopes and traditions of those below.

In rural China, where the practice of creating New Year paintings flourished, artisans would often incorporate zodiac animals and star patterns into their designs. Each year, a different animal from the Chinese zodiac takes center stage, but beyond these twelve creatures, the cosmos plays an equally important role. Farmers and villagers relied on the stars for agricultural timing, and this celestial dependency found its way into the art they cherished. The Big Dipper, for instance, frequently appears in these paintings, symbolizing guidance and fortune—a celestial compass pointing toward prosperity.

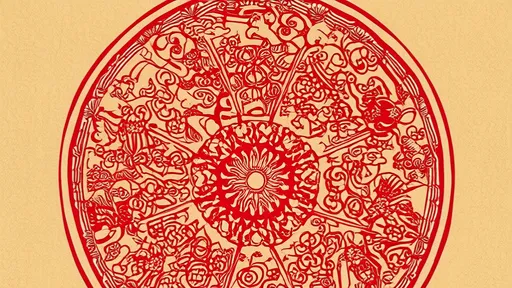

The craftsmanship behind these artworks is nothing short of extraordinary. Using woodblock printing techniques passed down through generations, artists would carve intricate designs into wooden plates, then layer them with bold pigments. The result was a striking visual narrative where constellations weren’t just distant lights but active participants in human affairs. A painting might show the Weaving Maid and the Cowherd, two star-crossed lovers from Chinese mythology, separated by the Milky Way yet forever bound in legend. Their story, often depicted during the Qixi Festival, would find its way into New Year art, blending seasonal celebration with cosmic romance.

What’s particularly intriguing is how these paintings served as both almanac and oracle. Before the widespread use of printed calendars, families would turn to New Year paintings to decipher auspicious dates or anticipate weather patterns. Certain constellations, when prominently featured, were believed to herald good harvests or warn of impending challenges. This practice underscores the intimate relationship between art and survival—a reminder that beauty and practicality were never mutually exclusive in traditional Chinese culture.

Today, as modern technology dominates timekeeping and astrology, the celestial themes in New Year paintings have taken on a more nostalgic role. Yet, their legacy endures. Contemporary artists revisiting this medium often infuse it with new interpretations, merging ancient star lore with modern aesthetics. Exhibitions showcasing these works draw crowds eager to reconnect with a heritage where the night sky wasn’t just observed but woven into the very fabric of daily life. The stars, it seems, will always have a place in the art of renewal—whether guiding a farmer’s plow or inspiring an artist’s brush.

The universality of celestial fascination makes these paintings resonate beyond cultural boundaries. Western audiences, for example, might recognize parallels between Chinese zodiac-themed Nianhua and medieval European astrological manuscripts. Both traditions sought to map human existence onto the stars, finding comfort in the idea that the heavens could offer clues to earthly dilemmas. This cross-cultural kinship highlights a shared human impulse to seek meaning in the cosmos, whether through intricate woodblock prints or illuminated parchment.

Preservation efforts for these artworks have gained momentum in recent decades, with museums and collectors recognizing their historical value. Unlike mass-produced posters, authentic New Year paintings bear the imperfections of handmade craftsmanship—slight misalignments in color layers or subtle variations in ink density that testify to their artisan origins. These “flaws” become part of the charm, much like the individual stars that form a constellation’s unique pattern. In preserving them, we safeguard not just art but a worldview where humanity and the universe were in constant dialogue.

Perhaps the most enduring lesson from these star-adorned paintings is their celebration of cyclical time. The zodiac’s twelve-year rotation and the constellations’ seasonal appearances mirror the endless loop of planting and harvest, of endings and beginnings. As each New Year arrives, these artworks remind us that while calendars may change, some connections—between earth and sky, tradition and innovation—remain unbroken. They invite us to look up, just as their creators did centuries ago, and find in the stars both a guide and a muse.

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025